AI evaluation is undergoing a paradigm shift from focusing solely on algorithmic accuracy of AI models to emphasizing experience-based assessment of human interactions with AI systems. Under frameworks like the EU AI Act, evaluation now considers intended purpose, risk, transparency, human oversight, and real-world robustness alongside accuracy. Quality of Experience (QoE) methodologies may offer a structured approach to evaluate how users perceive and experience AI systems in terms of transparency, trust, control and overall satisfaction. This column gives inspiration and shared insights for both communities to advance experience-based AI system evaluation together.

1. From algorithms to systems: AI as user experience

Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms—mathematical models implemented as lines of code and trained on data to predict, recommend or generate outputs—were, until recently, tools reserved for programmers and researchers. Only those with technical expertise could access, run or adapt them. For decades, progress in AI was equated with improvements in algorithmic performance: higher accuracy, better precision or new benchmark records—often achieved under narrow, controlled conditions that did not reflect the full spectrum of real-world operational environments. These advances, though scientifically impressive, remained largely invisible to society at large.

The turning point came when AI stopped being just code and became an experience accessible to everyone, regardless of their technical background. Once algorithms were embedded into interactive systems—chatbots, voice assistants, recommendation platforms, image generators—AI became ubiquitous, integrated into people’s daily lives. Interfaces transformed technical capability into human experience, making AI not only a purely algorithmic or research-oriented field but also a social, experiential and increasingly public phenomenon [Mlynář et al., 2025].

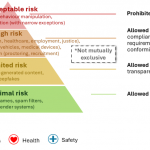

This shift fundamentally changed what it means to evaluate AI [Bach et al., 2024]. Accuracy-based metrics—such as precision, recall, specificity or F1-score—no longer suffice for systems that mediate human experiences, influence decision-making and shape trust. Evaluation must now extend beyond the model’s internal performance to assess the interaction, context and experience that emerge when humans engage with AI systems in realistic conditions. We must therefore move from evaluating algorithms in isolation to genuinely human-centered approaches to AI and the experiences it enables [see e.g., https://hai.stanford.edu/], evaluating AI systems as a whole, holistically—considering not only their technical performance but also their experiential, contextual, and social impact [Shneiderman, 2022]. The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act [AI Act, 2024] provides a clear illustration of this shift. As the first comprehensive regulatory framework for AI, it recognizes that while algorithmic quality remains essential, what is ultimately regulated is the AI system—its design, use, and intended purpose. Obligations under the Act are tied to that intended purpose, which determines both the risk level and the compliance requirements (see figure below). For instance, the same object detection model can be considered low risk when used to organize personal photo libraries, but high risk when deployed in an autonomous vehicle’s collision-avoidance system.

This illustrates a fundamental change: evaluating AI systems today requires understanding how, where and by whom a system is used—not merely how accurate its underlying AI model is. Moreover, evaluation must consider how systems behave and degrade under operational conditions (e.g., adverse weather in traffic monitoring or biased performance across demographic groups in facial analysis), how humans interact with, interpret and rely on them, and what mechanisms of human oversight or intervention exist in practice to ensure accountability and control [Panigutti et al., 2023].

2. Towards a paradigm shift in AI evaluation

The European AI Act marks the first comprehensive attempt to regulate the design, deployment and use of AI systems. Yet its underlying philosophy resonates broadly with the principles endorsed by other high-level international institutions and initiatives—such as the OECD [OECD, 2024], the World Economic Forum [WEF, 2025] and, more recently, the Paris AI Action Summit [CSIS, 2025], where over sixty countries signed a joint commitment to promote responsible, trustworthy and human-centric AI.

Among the many obligations set out in the AI Act for high-risk AI systems, three provisions stand out as emblematic of this paradigm shift: they focus not on algorithmic precision, but on how AI systems are experienced, supervised and operated in the real world.

- Article 13 – Transparency. AI systems must be designed and developed in a way that is sufficiently transparent to enable users to interpret their output and use it appropriately. Transparency therefore extends beyond disclosure or documentation: it encompasses interaction design and interpretability, ensuring that users—especially non-experts—can meaningfully understand and act upon what the system produces, based on which input and how.

- Article 14 – Human oversight. High-risk AI systems must allow for effective human supervision so that they can be used as intended and to prevent or minimise risks to health, safety or fundamental rights (e.g., respect for human dignity, privacy, equality and non-discrimination). Oversight involves not only control features or override mechanisms, but also interface designs that help operators recognise when human intervention is necessary—addressing known challenges such as automation bias and over-trust on AI systems [Gaudeul et al., 2024].

- Article 15 – Accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity. This provision broadens the traditional notion of accuracy, demanding that systems perform reliably under real-world operational conditions and remain secure and resilient to errors, adversarial manipulation or context change. It also calls for mechanisms that support graceful degradation and error recovery, ensuring sustained trust and dependable performance over time.

These provisions, aligned to both the AI Act and the broader international discourse on responsible AI, express a clear transformation in how AI systems should be evaluated. They call for a move beyond in-lab algorithmic performance metrics to include criteria grounded in human experience, operational reliability and social trust. To make these requirements actionable, the European Commission issued a Standardisation Request on Artificial Intelligence (initially published as M/593, 2024 [European Commission, 2024] and subsequently updated following the adoption of the AI Act), mandating the development of harmonised standards to support conformity with the regulation. Yet analyses of existing AI standardisation frameworks suggest that they remain primarily focused on technical robustness and risk management, while offering limited methodological guidance for assessing transparency, human oversight and perceived reliability [Soler et al., 2023].

This gap underscores the need for contributions from the Quality of Experience (QoE) community, whose expertise in assessing perceived quality, pragmatic, hedonic and increasingly also eudaimonic aspects of users’ experiences, usability and trust could inform both standardisation efforts and AI system design in practice. For example, [Hammer et al., 2018] introduced the “HEP cube”, that is a 3D model that maps hedonic (H), eudaimonic (E), and pragmatic (P) aspects of QoE and user experience. For example, utility (P), joy-of-use (H), and meaningfulness (E) are integrated into a multidimensional HEP construct [Egger-Lampl et al., 2019]. In professional contexts, long-term experiential quality depends increasingly on eudaimonic factors such as meaning and personal growth of the user’s capabilities. On the example of augmented reality for the informational phase of procedure assistance, [Hynes et al., 2023] take into account pragmatic aspects like clear, accurately aligned AR instructions that reduce cognitive load and support efficient task execution; hedonic and eudaimonic aspects involve engaging, intuitive interactions that not only make the experience pleasant but also foster confidence, competence, and meaningful professional growth. The study confirmed that AR better fulfills users’ pragmatic needs compared to paper-based instructions. However, the hypothesis that AR surpasses paper-based instructions in meeting hedonic needs was rejected. [Oppermann et al., 2024] evaluated a VR-based forestry safety training and found improved experiential quality and real-world skill transfer compared to traditional instruction. In addition to hedonic and pragmatic UX, eudaimonic experience was assessed by asking participants whether the training would help them “make me a better forestry worker” and “develop my personal potential”.

3. From benchmark performance to operational reality: the case of facial recognition

The example of remote facial recognition (RFR) for public security clearly illustrates how traditional accuracy-based evaluation fails to capture the real challenges of proportionality, operational viability and public trust that define the true quality of experience of AI in use. Under the EU AI Act, the use of real-time remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement is prohibited, except in narrowly defined circumstances—such as the prevention of terrorist threats, the search for missing persons or the prosecution of crimes—and always subject to prior authorisation by a competent authority. In these cases, the authority must assess whether the deployment of such a system is necessary and proportionate to the intended purpose.

Both the AI Act and the World Economic Forum emphasise this principle of “proportionality” for face recognition systems [AI Act, 2024], [Louradour & Madzou, 2021], yet without providing a clear guidance to determine what “proportionate use” actually means. Deciding whether to deploy RFR therefore requires balancing multiple dimensions—technical performance, societal impact and human oversight—beyond mere accuracy scores [Negri et al., 2024]. Consider, for instance, a competent authority evaluating whether to deploy an RFR system in airports screening 200 million passengers annually, where the estimated prevalence of genuine threats is roughly one in fifty million. Even with a true positive rate (TPR) and true negative rate (TNR) of 99% (equivalent to 99% sensitivity and specificity), the outcome is paradoxical: nearly all real threats would be detected (≈ 4 per year), but around two million innocent passengers would face unnecessary police interventions. Algorithmically, a 99% performance looks excellent. Operationally, it is unmanageable and counterproductive. Handling millions of false alarms would overwhelm security forces, delay operations, and—most importantly—erode public trust, as citizens repeatedly experience unjustified scrutiny and loss of confidence in authorities.

Beyond accuracy, competent authorities must evaluate trade-offs between different operational, social and economic dimensions that holistically define the proportionality and viability of an AI system:

- Operational feasibility: number of human interventions needed, false alarms to handle and system downtime.

- Social impact: perceived fairness, legitimacy and transparency of interventions.

- Economic cost: cost of system deployment, resources spent managing false positives versus genuine detections.

- Human trust and cognitive load: how repeated interactions with the system affect operator confidence, vigilance and the balance between over-trust and alert fatigue.

- Consequences of error: the cost of a missed detection versus that of an unjustified intervention.

Hence, accuracy alone cannot guarantee reliability or trustworthiness. Evaluating AI systems requires contextual and human-aware metrics that capture operational trade-offs and social implications. The goal is not only to predict well, but to perform well in the real world. This example reveals a broader truth: trustworthy AI demands evaluation methods that connect technical performance with lived experience—and this is precisely where the QoE community can make a distinctive contribution.

4. Where AI and QoE should meet: new metrics for a new era

The limitations of accuracy-based evaluation, as illustrated by the facial recognition case, point to a broader need for metrics that capture how AI systems perform in real-world, human-centred contexts [Virvou, 2023],[Park et al., 2023].

Over the past decades, the scientific communities focusing on QoE and user experience (UX) research have developed a rigorous toolbox for quantifying subjective experience—how users perceive quality, usability, pragmatic, hedonic and increasingly also eudaimonic aspects of users’ experiences, reliability, control and satisfaction when interacting with complex technological systems. Originally rooted in multimedia, communication networks and human–computer interaction, these methodologies offer a mature foundation for assessing experienced quality in AI systems. QoE-based approaches can help transform general principles such as transparency, human oversight and robustness into measurable experiential dimensions that reflect how users actually understand, trust and operate AI systems in practice.

The following table presents a set of illustrative examples of QoE-inspired metrics—adapted from long-standing practices in the field—that could be further adapted, developed and validated for the evaluation of trustworthy AI.

| General AI principles | QoE-inspired metrics |

| Transparency and comprehensibility | Perceived transparency score: % of users reporting understanding of system capabilities/limitations, potentially with a way to dimension the gap between reported understanding and actual understanding Explanation clarity MOS: Mean Opinion Score on clarity and interpretability of explanations. While traditional QoE assessment results are often reported as a Mean Opinion Score (MOS), additional statistical measures related to the distribution of scores in the target population are of interest, such as user diversity, uncertainty of user rating distributions, ratio of dissatisfied users, etc. [Hoßfeld et al., 2016] Time to comprehension: average time for a non-expert to understand the meaning of a given output produced by the system. Experienced interpretability: extent to which users feel that explanations meaningfully enhance their understanding of the system’s reasoning and limitations [Wehner et al., 2025]. |

| Human oversight | Perceived controllability: MOS on ease of intervening or correcting system behavior. Intervention success rate: % of interventions improving outcomes. Trust calibration index: alignment between user confidence and actual system reliability. |

| Robustness and resilience to errors | Perceived reliability over time: longitudinal QoE measure of stability (for example, inspired by work on the longitudinal development of QoE, such as [Guse, D., 2016], [Cieplinska, 2023]). Graceful degradation MOS: subjective quality under stress (e.g., noise, adversarial input). Error recovery satisfaction: % of users satisfied with post-failure recovery. |

| Experience quality (holistic) | Overall satisfaction MOS: overall perceived quality of interaction with the AI system and factors influencing that experience quality (human, system, context, as discussed in [Reiter et al.. 2014]. Smoothness of use: perceived fluidity, continuity, absence of frustration. Perceived usefulness and usability: e.g., adapted from widely-used SUS/UMUX-Lite scales [Lewis et al., 2013]. Perceived response alignment: capture to what extent the system response aligns semantically and contextually with the prompt intent (particularly relevant for generative AI systems). Cognitive load: mental effort perceived during operation (e.g., adapted NASA-TLX [Hart & Staveland, 1988]). Perceived productivity impact: how users perceive the effect of AI system assistance on task efficiency and cognitive effort, reflecting findings from recent large-scale developer studies [Early-2025 AI, AI hampers Productivity]. |

These examples illustrate how the QoE perspective can complement traditional performance indicators such as accuracy or robustness. They extend evaluation beyond technical correctness to include how people experience, trust and manage AI systems in operational environments. Of interest will be to further explore and model the complex relationships between identified QoE dimensions and underlying system, context and human influence factors.

To better illustrate such complex relationships, it is useful to consider how technical and experiential dimensions interact dynamically in use. One particularly relevant example concerns how AI systems communicate confidence or uncertainty, and how this shapes users’ perceived trustworthiness, engagement and overall Quality of Experience.

While this is only one example among many possible human–AI interaction dynamics, it illustrates the kind of interrelation that still requires deeper understanding. As depicted in the figure above, complex interrelations exist that are not yet fully understood. AI confidence calibration (based on the AI model) and the way how this confidence or uncertainty is transported to users influences the users’ perceived trustworthiness of the AI system. This impacts the user’s confidence to which degree a user trusts their own ability to understand, interpret, and effectively interact with the AI system. Poor calibration can trigger a negative feedback loop of mistrust and disengagement, while well-calibrated, transparent AI fosters a positive feedback loop that enhances trust, confidence, and effective human-AI collaboration. In a negative feedback loop, overconfidence leads to low perceived trustworthiness and a strong QoE decline, while underconfidence results in moderate perceived trustworthiness and medium QoE, ultimately lowering user engagement. In contrast, a positive feedback loop emerges when confidence is well-calibrated and aligns with accuracy or when uncertainty is expressed transparently, leading to high trust, higher QoE, and stronger user engagement. User engagement and QoE are closely interrelated [Reichl et al., 2015], as higher engagement often reflects and reinforces a more positive overall experience.

Following this and similar examples, the bridge that now needs to be built is between the AI community’s focus on algorithmic performance and the QoE community’s expertise in human experience, bringing together two perspectives that have evolved largely in isolation, but are inherently complementary.

5. Conclusions: QoE as part of the missing link between AI systems and real-world experiences

Bridging the gap between how AI systems perform and how they are experienced is now one of the most pressing challenges in the field. The AI community has achieved extraordinary advances in model accuracy, scalability and efficiency, yet these metrics alone do not fully capture how systems behave in context—how they interact with people, support oversight or sustain trust under real operating conditions. The field of QoE, with its long tradition of measuring perceived quality, different experiential dimensions and usability, offers the conceptual and methodological tools needed to evaluate AI systems as experienced technologies, not merely as computational artefacts.

In this context, QoE of AI systems can be adapted from the original definition of QoE as proposed in [Qualinet, 2013] to read as: “The degree of delight or annoyance of a user resulting from interacting with an AI system. It results from how well the AI system fulfills the user’s expectations regarding usefulness, transparency, trustworthiness, comprehensibility, controllability, and reliability, considering the user’s goals, context, and cognitive state.”

Collaborative research between these domains can foster new interdisciplinary methodologies, shared benchmarks and evidence-based guidelines for assessing AI systems as they are used in the real world—not just as they perform in the lab or within classical accuracy-centred benchmarks. Building this shared evaluation culture is essential to advance trustworthy, human-centric AI, ensuring that future systems are not only intelligent but also understandable, reliable and aligned with human values.

This need is becoming increasingly urgent as, in many regions such as the EU, the principles of trustworthy AI are evolving from ethical aspirations into formal regulatory requirements, reinforcing the importance of robust, experience-based evaluation frameworks.

References

- [AI Act, 2024] European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/1020 and Directives (EU) 2015/1535 and 2017/745 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union, L 2024/1689. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj

- [AI hampers Productivity] Experienced software developers assumed AI would save them a chunk of time. But in one experiment, their tasks took 20% longer. Available at: https://fortune.com/2025/07/20/ai-hampers-productivity-software-developers-productivity-study/

- [Bach et al., 2024] Bach, T. A., Khan, A., Hallock, H., Beltrão, G., & Sousa, S. (2024). A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: An HCI perspective. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(5), 1251-1266.

- [Cieplinska, 2023] Cieplínska, Natalia; Janowski, Lucjan; Moor, Katrien De; Wierzchoń, Michał. (2023) Long-Term Video QoE Assessment Studies: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access.

- [CSIS, 2025] Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2025). France’s AI Action Summit. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/frances-ai-action-summit

- [Early-2025 AI] Measuring the Impact of Early-2025 AI on Experienced Open-Source Developer Productivity. Available at: https://metr.org/blog/2025-07-10-early-2025-ai-experienced-os-dev-study/

- [Egger-Lampl et al., 2019] Egger-Lampl, S., Hammer, F., & Möller, S. (2019). Towards an integrated view on QoE and UX: adding the Eudaimonic Dimension. ACM SIGMultimedia Records, 10(4), 5-5.

- [European Commission, 2024] European Commission. (2023). C(2023)3215 – Standardisation request M/593 to the European Committee for Standardisation and the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation in support of Union policy on artificial intelligence. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/enorm/mandate/593_en

- [Gaudeul et al., 2024] Gaudeul, A., Arrigoni, O., Charisi, V., Escobar-Planas, M., & Hupont, I. (2024, October). Understanding the Impact of Human Oversight on Discriminatory Outcomes in AI-Supported Decision-Making. In 27th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence (pp. 19-24).

- [Guse, D., 2016] Guse, D. (2017). Multi-episodic perceived quality of telecommunication services. PhD thesis, TU Berlin.

- [Hammer et al., 2018] Hammer, F., Egger-Lampl, S., & Möller, S. (2018). Quality-of-user-experience: a position paper. Quality and User Experience, 3(1), 9.

- [Hart & Staveland, 1988] Hart, S. G., & Staveland, L. E. (1988). Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In Advances in psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 139-183). North-Holland.

- [Hoßfeld et al., 2016] Hoßfeld, T., Heegaard, P. E., Varela, M., & Möller, S. (2016). QoE beyond the MOS: an in-depth look at QoE via better metrics and their relation to MOS. Quality and User Experience, 1(1), 2.

- [Hynes et al., 2023] Hynes, E., Flynn, R., Lee, B., & Murray, N. (2023). A QoE evaluation of augmented reality for the informational phase of procedure assistance. Quality and User Experience, 8(1), 1.

- [Lewis et al., 2013] Lewis, J. R., Utesch, B. S., & Maher, D. E. (2013, April). UMUX-LITE: when there’s no time for the SUS. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 2099-2102).

- [Louradour & Madzou, 2021] Louradour, S. & Madzou, L. (2021). A policy framework for responsible limits on facial recognition, use case: Law enforcement investigations. In World Economic Forum, 2021.

- [Mlynář et al., 2025] Mlynář, J., De Rijk, L., Liesenfeld, A., Stommel, W., & Albert, S. (2025). AI in situated action: a scoping review of ethnomethodological and conversation analytic studies. AI & society, 40(3), 1497-1527.

- [Negri et al., 2024] Negri, P., Hupont, I., & Gomez, E. (2024, May). A framework for assessing proportionate intervention with face recognition systems in real-life scenarios. In 2024 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition.

- [OECD, 2024] OECD Legal Instruments. (2024). Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence.

- [Oppermann et al., 2024] Oppermann, M., Schatz, R., Sackl, A., & Egger-Lampl, S. (2024, June). Virtual Forests, Real Skills: Assessing the QoE of VR-based Occupational Training and its Impact on Experience and Learning Outcomes. In 2024 16th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX) (pp. 250-253). IEEE.

- [Panigutti et al., 2023] Panigutti, C., Hamon, R., Hupont, I., Fernandez, D., Fano, D., Junklewitz, H., … & Gomez, E. (2023, June). The role of explainable AI in the context of the AI Act. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (pp. 1139-1150).

- [Park et al., 2023] Park, S., Kim, H. K., Park, J., & Lee, Y. (2023). Designing and evaluating user experience of an AI-based defense system. IEEE Access, 11, 122045-122056.

- [Shneiderman, 2022] Schneiderman, B. (2022). Human-centered AI. Oxford University Press. Online ISBN: 9780191937583

- [Qualinet, 2013] Qualinet White Paper on Definitions of Quality of Experience (2012). European Network on Quality of Experience in Multimedia Systems and Services (COST Action IC 1003), Patrick Le Callet, Sebastian Möller and Andrew Perkis, eds., Lausanne, Switzerland, Version 1.2, March 2013.

- [Reichl et al., 2015] Reichl, P. et al. (2015). Towards a comprehensive framework for QoE and user behavior modelling. In 2015 seventh international workshop on quality of multimedia experience (QoMEX) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- [Reiter et al.. 2014] Reiter, U. et al. (2014). Factors Influencing Quality of Experience. In: Möller, S., Raake, A. (eds) Quality of Experience. T-Labs Series in Telecommunication Services. Springer, Cham.

- [Soler et al., 2023] Soler, J., Tolan, S., Hupont, I., Fernandez, D., Charisi, V., Gomez, E., Junklewitz, H., Hamon, R., Fano, D. and Panigutti, C., AI Watch: Artificial Intelligence Standardisation Landscape Update, EUR 31343 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, ISBN 978-92-76-60450-1, doi:10.2760/131984, JRC131155.

- [Virvou, 2023] Virvou, M. Artificial Intelligence and User Experience in reciprocity: Contributions and state of the art. Intelligent Decision Technologies, 17(1), 73-125.

- [WEF, 2025] World Economic Forum. (2025). AI Governance Alliance.

- [Wehner et al., 2025] Wehner, N., Seufert, A., Hoßfeld, T. and Seufert, M. (2025). A Tutorial on Data-Driven Quality of Experience Modeling With Explainable Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, doi: 10.1109/COMST.2025.3583227.

![Figure 1. Screenshot from SoundCloud showing a list of timed comments left by listeners on a music track [11].](http://sigmm.hosting.acm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/figure1_datasets.png)

![Figure 2. Screenshot from SoundCloud indicating the useful information present in the timed comments. [11]](http://sigmm.hosting.acm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/figure2_datasets1.png)

![Figure 3. Screenshot from SoundCloud indicating the noisy nature of timed comments [11].](http://sigmm.hosting.acm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/figure3_datasets1.png)